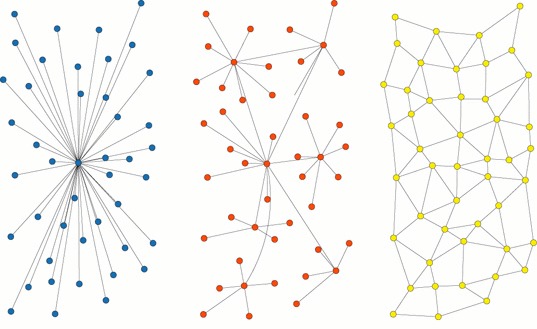

name: inverse layout: true class: center, middle, inverse --- # Introduction to version control and Git ## Radovan Bast Licensed under [CC BY 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Code examples: [OSI](http://opensource.org)-approved [MIT license](http://opensource.org/licenses/mit-license.html). --- layout: false <img src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/gh/coderefinery/lessons@0c5dc881e5052a111a8d25909f8d99b67807cd2d/img/git/intro/git-fire.jpg" style="width: 600px;"/> --- ## What we will learn in this lesson - Why version control - Why Git - Configuring Git - Basic Git workflow - Linear and local development - Using the staging area - Undoing things --- template: inverse # Why version control and why Git? --- ## Version control - Very often we work on projects where versions are useful or important - Programs - Scripts - Configuration files - Websites - Manuscripts - Have you ever made a backup copy of source files before modifying them? ```shell $ cp complicated.py complicated.py.backup $ vi complicated.py ``` - Have you ever wished you had done a backup copy before you completely broke a source code and had to start over? - Programming is an iterative process - When you code typically there comes a point where the code gets broken - It would be nice to be able to go back --- template: inverse ## How many of you have used the "undo" button when you edit a document? --- ## Version control - A version control system (VCS; or revision control) is a framework that tracks the versions of a project ``` [1] --> [2] --> [3] --> [4] --> [5] --> [6] --> [7] --> [8] --> [9] --> ... ``` - Like save points in computer games - We archive the current state - We keep all past revision - We can go back to arbitrary revision - We can compare revisions - Compare with Apple Time Machine - The simplest VCS would be to copy the entire project somewhere and give it a revision number/name --- ## Example: Poor man version control ```shell MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_10.8.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.4_18.3.07.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_17.5.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.4_27.7.07.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_23.8.07_final.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.4_29.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_24.5.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.4_6.10.07.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_25.5.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.5_23.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_29.5.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.5_25.5.07.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_30.5.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.5_6.6.07.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_6.10.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.5_bexC.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_6.6.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.2.5_D0.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_CP_8.6.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.0_4.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_KT.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.1_4.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_PI1_2007.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.2_22.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_PI_2007.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.2_4.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_PI2_2007.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.2_5.4.08.tgz MAG-DKS2-RI_PI_CP_18.3.07.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.3_1.5.08.tgz MAG-mDKS_11.5.08.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.3_20.5.08.tgz MAG-mDKS_15.4.08.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.3_TSTrm_27.6.08.tgz MAG-mDKS_17.6.09_unfinished.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.3_WK_10.8.08.tgz MAG-mDKS_19.7.09.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.3_WK_11.8.08.tgz MAG-mDKS-20.7.09.tgz ReSpect-AFDZ-1.3.3_WK_13.8.08.tgz ... ``` - Merges need to be done manually - Difficult to inspect the project history (e.g.: at which point was a bug introduced?) - Almost impossible to keep track of patches --- ## Motivation for version control: collaboration <img src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/gh/coderefinery/lessons@0c5dc881e5052a111a8d25909f8d99b67807cd2d/img/git/intro/phd_final.gif" style="width: 400px;"/> --- ## Motivation for version control: collaboration ### Collaborative work - Programs are often developed by many people in parallel - It would be extremely tedious to synchronize this work manually - We write manuscripts with collaborators ("can you please send me the last version?") - Have you ever waited for your collaborator before making changes to a manuscript? - Imagine you are the corresponding author and publish a paper with 20 collaborators - Version controls enables us to work with several people on the same code at the same time - Without the need for manual synchronization - Without the risk of undoing the work of others by accident - For manuscripts we recommend https://www.overleaf.com --- ## Motivation for version control ### Sharing code with others - Many of us distribute our programs to users - Git simplifies this process - Easy to share updates and patches - Lowers the barrier for new developers to contribute to our code ### Scientific reproducibility - Versions are essential for reproducibility of published computational results - We use scientific code to produce scientific results - These programs evolve, bugs appear and get fixed - It is essential that we can easily access and compare versions of our program --- ## Additional motivation for version control ### Version control is also great in a one-(wo)man universe - Often we work on the same thing from different computers/devices - There are many USB sticks that commute between home and office - We can use Git as a "Dropbox" --- ## Version control market - https://www.openhub.net/repositories/compare - Not fully representative but gives an idea --- ## Centralized vs. decentralized vs. distributed  - CVS and Subversion are centralized (one server keeps track of versions, working copies are clients) - Git, Mercurial, and Bazaar are distributed (every working copy can keep track of versions) - We will see later why distributed is often better for scientific code development --- ## Why we will choose Git (1/2) - Git is a distributed VCS - But supports any workflow (also legacy centralized modes of operation) - Written by Linus Torvalds - Fast and lightweight - Nearly every operation is done offline on your local disk - You can do commits, diffs, logs, branches, merges, annotation and more entirely offline - Merging development lines is trivial and fun - You get reasonable backup for free (because entire project history is distributed) --- ## Why we will choose Git (2/2) - Prominent companies and projects using Git: Linux Kernel, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, Linkedin, Netflix, Perl, PostgreSQL, ALSA, Android, Fedora, GCC, GNU Autotools, GNOME, phpMyAdmin, Ruby on Rails, Samba, VLC, Wine, X11, Yum, ... - It is the version control tool with the most traction - GitHub - "Git is a four-handle, dual boiler espresso machine, not instant coffee". - DAG - Immutable objects --- template: inverse # Configuring Git --- ## Before we start working with Git - Before we use Git, let us configure Git on our machine for optimum Git experience - Colorize your life ```shell $ git config --global color.branch auto $ git config --global color.diff auto $ git config --global color.status auto ``` - Identify yourself, set your name and your e-mail (this will show up in the log history) ```shell $ git config --global user.name "Slim Shady" $ git config --global user.email slim.shady@gmail.com ``` - Set the default mode for `git push` - Avoids typing `git push origin <branch>` ```shell $ git config --global push.default current ``` - These settings are stored in `~/.gitconfig` --- ## Before we start working with Git - Set your favourite editor ```shell $ git config --global core.editor "vim" ``` - Here are my settings ```shell $ cat ~/.gitconfig [color] branch = auto diff = auto grep = auto status = auto [user] name = Radovan Bast email = rbast@users.noreply.github.com [push] default = current [core] editor = vim ``` - We set these only once on a computer and the settings will be global to all Git projects --- template: inverse # Basic Git workflow --- ## Git basics - How to initialize a new Git repository - How to add and commit files - How to inspect the project history - How to write useful commit log messages --- ## Exercising a basic Git cycle - Write a haiku and track it with Git (we do this together interactively in the terminal) ```shell On a branch ... by Kobayashi Issa On a branch floating downriver a cricket, singing. ``` --- ## Exercising a basic Git cycle ```shell $ git init $ git add $ git status $ git commit -m "commit message" $ git diff $ git log $ git show ``` - Everything in this course we will do with Git to get it into muscle memory --- ## Git basics - We can browse the development and access each state that we have committed - The long hashes uniquely label a state of the code - They are non-incremental (why?) - We will use them when comparing versions and when going back in time - `git log --oneline` is nice to get an overview - `git log --oneline` only shows the first 7 characters of the commit hash - If the first characters of the hash are unique it is not necessary to type the entire hash - `git log --stat` is nice to show which files have been modified (not shown because here we only have one file) --- ## Commit messages - We now understand that the first line of the commit message is very important - Good example ``` implement Pulay DIIS algorithm implement Pulay DIIS algorithm to accelerate SCF convergence and set it as default this is based on [REF] this option can be deactivated with .NODIIS ... ``` - Convention: one line summarizing the commit, then one empty line, then paragraph(s) with more details in free form, if necessary - Not so good example (everything in one long line): ``` implement Pulay DIIS algorithm to accelerate SCF convergence and set it ... ``` - This is also important for web based repository browsing --- ## Commit messages - Another bad example ``` rbast: fixed an important bug for contracted basis sets ... ``` - Other bad commit messages: "fix", "oops", "save work", "foobar", "toto", "qppjdfjd", "" - http://whatthecommit.com - Write commit messages in english that will be understood 15 years from now by someone else than you - Many projects start out as projects "just for me" and end up to be successful projects that are developed by 50 people over decades --- ## Commit messages - It is possible to commit and set commit message at the same time ```shell $ git commit -m "here I have changed this and that" ``` - This does not open any editor and commits directly --- ## Git basics - At any moment we can inspect individual commits ```shell $ git show 49dc419 commit 49dc419c8a44051cfe7826b85ee0a23e5faf3975 Author: Radovan Bast <rbast@users.noreply.github.com> Date: Sat Nov 22 15:33:15 2014 +0100 do not recompute powers diff --git a/triangle.py b/triangle.py index cc52fe2..fa35eab 100644 --- a/triangle.py +++ b/triangle.py @@ -6,7 +6,10 @@ m = int(sys.argv[1]) # loop over all a < b < c <= m for c in xrange(1, m+1): + cp = c*c for b in xrange(1, c): + bp = b*b for a in xrange(1, b): - if a*a + b*b == c*c: + ap = a*a + if ap + bp == cp: print("(%i, %i, %i)" % (a, b, c)) ``` - We see that the start of the hash is enough if it is unique --- ## Git basics - Now we know how to save versions ```shell $ git add <file(s)> $ git commit ``` - And this is what we do as we program - Every state is then saved and later we will learn how to go back to these "checkpoints" and how to undo things - We could live a fulfilled life with the following few Git commands ```shell $ git init # initialize new repository $ git add # add files or stage file(s) $ git commit # commit staged file(s) $ git status # see what is going on $ git log # see history $ git diff # show unstaged/uncommitted modifications $ git show # show the change for a specific commit $ git mv # move tracked files $ git rm # remove tracked files ``` --- ## Where is the Git repository? - All the magic is under `.git`, all the history, all snapshot, all branches, everything - When we staged and committed files, we "copied" them into `.git` - Here we only track one file but we can track entire file trees - Git does not pollute subdirectories - If we remove `.git`, we remove the repository (but of course keep the working directory) - It is very easy to create (and remove) a Git repository to track something that you work on - `.git` uses relative paths (very convenient), you can move the whole thing somewhere else and it will still work --- ## Ignoring files ```shell $ git status # On branch master ... # # Untracked files: # (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed) # # a.out ``` - Files that are not supposed to be tracked belong in `.gitignore` (object files, compiled code, generated files, \*.pyc files, generated \*.pdf files) - `.gitignore` understands regular expressions and is valid for all subdirectories - Use `.gitignore` otherwise `git status` is flooded with untracked files and useless - People who do not use `git status` make mistakes (e.g. forget to add files) - You should track `.gitignore` (do not ignore it) --- ## Ignoring files - Here is an example `.gitignore` file from another project ```shell $ cat .gitignore _build/ build*/ *.pyc ``` - It is possible to ignore entire directories ### Clean working area - Use `git status` a lot - Use `.gitignore` - Untracked files belong to .gitignore - **All** files should either be tracked or ignored --- template: inverse # Using the staging area --- ## Three level system - Before we continue we recall that we have committed changes in two steps - We have used `git add` and `git commit` - In Git we work in a 3-level system (for very good reasons as we shall see) - Working directory (your usual directories and files) - Staging area (preparation for next commit) - HEAD (last commit) ```shell $ git add # working directory --> staging area $ git commit # staging area becomes the new commit (HEAD) ``` --- ## It is useful to have a nice and readable history - Bad example ```shell b135ec8 now feature A should work 72d78e7 fix for parallel compilation bf39f9d bugfix 49dc419 removed too much 45831a5 removing debug print bddb280 more work on feature B 72e0211 another fix to make it compile e2073c3 oops! forgot another file 61dd3a3 forgot file a9f5172 save work on feature A 6fe2f23 save work on feature B ``` - Very often you will be obliged to do archaelogy in your code - Imagine that in few months you discover that feature B was a mistake - It is very difficult to find and revert this in this example --- ## Master should have a nice and readable history - Good example ```shell 6f0d49f feature C fee1807 feature B 6fe2f23 feature A ``` - We want to have nice commits - But we also want to "save often" (checkpointing) - how can we have both? - We will now learn to fabricate nice commits using the staging area --- ## Checkpointing using the staging area ```shell working staging HEAD command directory area | english | | | *git add file(s) |--------->| | stage file *git commit | |--------->| commit staged file(s) git commit file(s) |-------------------->| commit file(s) directly *git diff |<-------->| | between workdir and staged git diff --cached | |<-------->| between staged and last commit git diff HEAD |<------------------->| between workdir and last commit git diff |<------------------->| if nothing is staged git reset |<---------| | unstage git reset --soft | |<---------| "uncommit" and stage git reset --hard |<--------------------| discard *git checkout |<---------| | undo unstaged modifications git checkout |<--------------------| if nothing is staged ``` - `git add` every change that improves the code - `git checkout` every change that made things worse - `git commit` as soon as you have created a nice self-contained unit (not too large, not too small) - Discuss/think about what is too large or too small --- ## Checkpointing using the staging area - We want to do many small commits (checkpoints) - But at the end we want to commit in one nice commit - With `git add` we can prepare commits ```shell $ git add file.py # checkpoint 1 $ git add file.py # checkpoint 2 $ git add another_file.py # checkpoint 3 $ git add another_file.py # checkpoint 4 $ git diff another_file.py # diff w.r.t. checkpoint 4 $ git checkout another_file.py # oops go back to checkpoint 4 $ git commit # commit everything that is staged ``` - `git diff` gives differences with respect to the staging area, this is very practical - Using `git add` we can fabricate very nice coherent commits --- ## Staging everything - Sometimes you want to stage all modifications - No need to stage them one by one ```shell $ git add -u ``` - Also removals of tracked files are then automatically staged --- ## Working without the staging area ```shell working staging HEAD command directory area | english | | | git add file(s) |--------->| | stage file git commit | |--------->| commit staged file(s) *git commit file(s) |-------------------->| commit file(s) directly git diff |<-------->| | between workdir and staged git diff --cached | |<-------->| between staged and last commit git diff HEAD |<------------------->| between workdir and last commit *git diff |<------------------->| if nothing is staged git reset |<---------| | unstage git reset --soft | |<---------| "uncommit" and stage git reset --hard |<--------------------| discard git checkout |<---------| | undo unstaged modifications *git checkout |<--------------------| if nothing is staged ``` --- template: inverse # Undoing things --- ## Undoing things - In the following (interactive demo) we will learn how to revert code changes that - have not yet been staged - have been staged but not committed - have been committed --- ## Correcting incomplete commits - Imagine we just committed something but realize that the commit is incomplete - For instance we forgot to add a file - `git commit --amend` adds staged changes to the previous commit - If nothing is staged, we can use `git commit --amend` to modify the last commit message (e.g. to fix a horrible typo) - This does not modify the actual commit content but opens up the message editor and lets you change it - `git commit --amend` replaces the last state with a new commit (and a new hash) - **Never use git commit --amend on commits that you have shared with others** (more about this later) --- ## "Deleting" commits - In Git it is possible to remove commits ```shell $ git log --oneline ce373ff another terribly terrible error 87c9a94 a horribly embarrassing mistake 0a31903 make it possible to test Fermat Theorem bf39f9d break loop a if triple found 49dc419 do not recompute powers 45831a5 read upper limit from stdin 4fc4b95 print Pythagorean triples up to c = 20 ``` - Imagine we want to go back to commit `0a31903` and completely remove commits `87c9a94` and `ce373ff` - This is possible with `git reset --hard` and `git reset --soft` ```shell $ git reset --hard 0a31903 $ git log --oneline 0a31903 make it possible to test Fermat Theorem bf39f9d break loop a if triple found 49dc419 do not recompute powers 45831a5 read upper limit from stdin 4fc4b95 print Pythagorean triples up to c = 20 ``` --- ## "Deleting" commits - **It is called --hard because it is dangerous, use with caution!** - The repository and the working tree is reset to state `0a31903` - All uncommitted changes will be lost for good! - It can be also useful if you want to reset your working tree to last committed state (HEAD) ```shell $ git reset --hard HEAD # DANGEROUS ``` - With `git reset --soft` you can "delete" commits, but you keep the code changes - `git reset --soft` puts your deleted commits into the staging area - **Never use git reset --soft or --hard on commits that you have shared with others** - Doing so would create conflicts for people who base their work on commits that you have deleted (more about it later) - You can always do a `git revert` (it does not replace old commits, it does not change history) - `git revert` is the only safe option to undo changes that are shared with others --- template: inverse # Summary --- ## Summary - We have learned basic Git commands - We have practiced the basic `git init; git add; git commit` workflow - We have not explored the true power of Git: branches - In the following we will learn how to: - How to work with branches - How to work with others - How to go back in time - And much more --- ## Backup and cloud - Git is not ideal for large binary files (for this consider http://git-annex.branchable.com/) - To synchronize unversionned large binary files among computers - Google drive - Dropbox - SpiderOak - Free cloud hosting of Git projects - https://github.com - https://gitlab.com - https://bitbucket.org - We will learn about GitHub later during the course --- ## Git and Subversion - With `git-svn` you can use Git commands/workflows together with a Subversion server ## Git and CVS - `git-cvsserver` - A CVS server emulator for Git